Nutrigenomics: a Piece of the Precision Nutrition Puzzle for IBD

Danielle Gaffen, MS, RDN, LD

- Last Updated

While there is general agreement that the typical “Western diet” may contribute to the increasing prevalence of IBD, as you may already know, unfortunately, research has NOT shown one diet or eating pattern that can help ALL people with IBD. [1]

The elimination diets you may have heard of or tried, such as the Specific Carbohydrate Diet, the CD-ED Diet, and more are starting to be studied and researched in greater depth and better designed studies …but more research is needed as scientists have found that certain dietary approaches may help some people with IBD but not others, and many of these eating patterns can be quite restrictive in nature.

Different guts tolerate different foods differently with this condition. Your food triggers may be WAY different than other people’s food triggers with IBD. For example, one of my husband’s biggest food triggers is dairy. However, I’ve had clients who have tolerated dairy just fine!

So the question boils down to this: if different guts with IBD tolerate different foods differently, how do you know what your particular gut can tolerate?

Right now, one of the most helpful tools we have is a symptom food journal. But what if there was more? What if we had the tools, based on science, to know what foods would agree with your gut and which foods would trigger symptoms for your particular gut and condition?

That’s where a concept, called Precision Nutrition comes in. Precision Nutrition encompasses three different areas: your genetics, a related field called epigenetics, and the microbiome.

This blog today is focusing on one piece of that Precision Nutrition puzzle: Nutrigenomics.

Genetics

As you may be aware, IBD tends to run in families, so if you or a close relative has the disease, your family members have an increased chance of developing Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. Studies have shown that between 5% and 20% of people with IBD have a first-degree relative, such as a parent, child, or sibling, who also has one of the diseases.

Interestingly, the genetic risk seems to be greater with Crohn’s disease than ulcerative colitis. [2]

Now, let’s break down genetics a bit further:

An international research effort called the Human Genome Project, which worked to determine the sequence of the human genome and identify the genes that it contains, estimated that humans have between 20,000 and 25,000 genes. The human genome project gave us the blueprint of how heredity is determined.

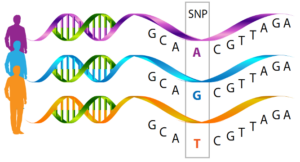

Now what I want to draw your attention to is this image of 3 genetic sequences in 3 separate people:

The sequence of these genes looks the same with G, C, and A, but when you get to the box, you can see that the letters that these three humans have are all different — there was a substitution made there, a slight change…at this specific location on the gene, think of it like a physical address on the gene, all three of these individual’s genes are different.

Now what does this mean? For the most part, that one change may not make a difference at all. But one reason why humans can be so metabolically different from one another is that each of us of has 40 to 50,000 of these variant spellings in our genes.

And when you put all of them together, looking at certain metabolic pathways in the body, these gene spellings can have a big impact on health.

For IBD specifically, scientists have found more than 240 of these different spellings so far that have been associated with a predisposition for developing the disease. These different spellings are called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs for short. [3]

So, you may be thinking here – that’s nice that scientists discovered that, but how does that relate to nutrition?

And I’m glad you asked because that’s where this area of nutrition called “nutrigenomics” comes in. Let’s break down that word, since nutrigenomics is a total jargon word.

So nutri- refers to nutrients or nutrition, and genomics refers to genes…so nutrigenomics refers to how nutrients interact with genes, especially with regard to the prevention or treatment of the disease.

Here are a few examples to share the current state of nutrigenomic research for IBD:

1. Beta Carotene into Vitamin A

One example of a nutrient whose absorption in the digestive system can be impacted by a person’s genes is beta-carotene, which is the orange-colored pigment and nutrient found in carrots (and many other foods)! When we eat foods with beta-carotene, like carrots, it’s our body’s job to transform the beta carotene into vitamin A.

But why I’m bringing this up is that researchers identified a gene, the BCM01 gene, that encodes a protein which is an important enzyme in the metabolism of the nutrient beta carotene to vitamin A. Interestingly, the presence of a SNP or misspelling of this BCMO1 gene, disrupts the normal efficient conversion of beta carotene to vitamin A, meaning that the beta carotene from the foods eaten like carrots is not going to be digested properly and give the body with the SNP the normal amount of vitamin A it would have without that misspelling. [4]

And this is a big deal, because consumption of adequate vitamin A has a lot of functions in our body, but what we really care about for IBD is how necessary vitamin A is for the immune system to function properly. A vitamin A deficiency could lead to gut lining dysfunction and inflammation, which are hallmarks of IBD.

So this is a pretty good example of what using a personalized dietary approach could look like with precision nutrition – while the presence of this SNP won’t automatically mean that a person will have a vitamin A deficiency, it could mean that a person is at risk for one. So if a person has this SNP and also a vitamin A deficiency, we could potentially tailor nutrition advice to it and recommend getting enough vitamin A from other, non-beta carotene food sources.

2. Fructose

There’s a lot of debate in the research publications about the effects of fructose consumption, and it’s been widely discussed by researchers that the increased consumption of fructose over the past 7 decades has contributed to the prevalence of IBD. [5] For those unaware of fructose, the biggest source of consumption in the United States is with high fructose corn syrup.

The reason I bring up fructose though is because the gene expression of TXNIP has been linked to fructose – specifically, the more fructose is consumed, the more this TXNIP gene may be expressed. But, in people with UC who have inflammation in the lining of their colon, a certain misspelling or SNP made the TXNIP gene expressed less, but not more with the fructose consumption. [6]

The relationship between fructose intake and the specific variation of the TXNIP gene may explain why fructose intake has been linked to intestinal symptoms of bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fructose intolerance in some individuals with IBD.

3. Brassica Vegetables

Some examples of brassica veggies include broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, and Brussel sprouts. Two randomized controlled diet studies found different responses in individuals depending on GSTMl gene expression. In GSTMl gene-positive individuals, inflammation increased with brassica vegetable intake. But in people with GSTMl gene-negative genotype, this did not occur. [7,8]

This is interesting because as you know with IBD, different guts tolerate different foods differently. If you knew you were GSTMI positive or negative, it could drive the nutrition prescription to either include or exclude these Brassica vegetables.

4. Mushrooms

One final example of a nutrigenomic study is how researchers found a SNP on the OCTN1 gene – and in people with Crohn’s disease, this variant was associated with mushroom intolerance compared to the general population. [9]

So that was a taste of nutrigenomics. But what does it really mean for you? The four research studies mentioned above present a commonality – certain foods could potentially trigger inflammation for certain people with IBD who have a specific gene variation, a specific SNP.

Knowing this could potentially help you identify if that food is contributing to symptoms experienced, and then potentially help tailor nutrition advice to make sure you’re getting the recommended amount of nutrients your body needs.

More Research is Needed

However, there are a few caveats that prevent this information from being ready to use right now:

1) More research is needed in this area: this field is pretty new, and we need more definitive and comprehensive links made for this information to be more helpful.

2) On a logistical note, while it’s getting cheaper to have your entire genetic code sequenced, it’s still very expensive. The gene sequencing you get from a company like 23andMe or Ancestry.com, is only a cross section of someone’s genome, not the entire DNA sequence. And that cross section does not look at the IBD related SNPs we are interested in or talked about today in this presentation (I checked for my husband’s sake). Gene sequencing of the entire genome is still cost prohibitive for the average person and no company exists that will only check the IBD SNPs.

3) And finally, we’re learning that Precision Nutrition for IBD includes more than just Nutrigenomics. Epigenetics and Microbiomics are additional pieces of the Precision Nutrition Puzzle. Stay tuned for future blog posts on these topics, or catch my presentation to the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation to learn more about these new and exciting fields of research for people with inflammatory bowel disease.

So what does this all mean – both right now and in the future?

As of right now, Nutrigenomics and Precision Nutrition for people with IBD are not ready for clinical practice. The science is just not there yet. While you can see that nutrigenomics has a lot of potential for people with IBD, with exciting discoveries of which foods may be associated with beneficial effects and which foods may be associated with adverse effects, there really is not enough diet information yet to create a food prescription, if you will.

We need more nutrigenomics studies linking more IBD SNPs with food intolerances. We need DNA sequencing to become less expensive. And we need more information about the other pieces of the Precision Nutrition puzzle, like epigenetics and how we can potentially improve the gut microbiome for people with IBD specifically.

But that being said, with each new study that is being published, we’re getting closer to hopefully answer the question, what should I eat with IBD?

Want more information about Precision Nutrition Research for IBD?

Catch my live Zoom presentation with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation on Thursday, October 14th at 5:30pm PST.

Click here to learn more and register.

Looking for some practical approaches for eating in IBD that you can do in the meantime as we wait for more research?

I help my clients implement a highly personalized nutrition plan that brings clarity around which foods to add that may be beneficial, reduces fear and anxiety around eating, lowers inflammation, and ultimately helps them get their lives back.

Click here to apply for a complimentary 30-minute virtual consultation:

References:

- Ashwin N. Ananthakrishnan, Gilaad G. Kaplan, Siew C. Ng, Changing Global Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Sustaining Health Care Delivery Into the 21st Century, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Volume 18, Issue 6, 2020, Pages 1252-1260, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.01.028

- Loddo I, Romano C. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Genetics, Epigenetics, and Pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:551. Published 2015 Nov 2. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00551

- Hu, S., Uniken Venema, W.T., Westra, HJ. et al.Inflammation status modulates the effect of host genetic variation on intestinal gene expression in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Commun 12, 1122 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21458-z

- Leung W., Hessel S., Meplan C., Flint J., Oberhauser V., Tourniaire F., Hesketh J., Von Lintig J., Lietz G. Two common single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding Β-Carotene 15, 15′-monoxygenase alter Β-carotene metabolism in female volunteers. FASEB J. 2009;23:1041–1053. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121962

- Laing BB, Lim AG, Ferguson LR. A Personalised Dietary Approach-A Way Forward to Manage Nutrient Deficiency, Effects of the Western Diet, and Food Intolerances in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1532. Published 2019 Jul 5. doi:10.3390/nu11071532

- Takahashi Y., Masuda H., Ishii Y., Nishida Y., Kobayashi M., Asai S. Decreased Expression of Thioredoxin Interacting Protein mRNA in Inflamed Colonic Mucosa in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Rep. 2007;18:531–536. doi: 10.3892/or.18.3.531.

- Campbell B., Han D.Y., Triggs C.M., Fraser A.G., Ferguson L.R. Brassicaceae: Nutrient Analysis and Investigation of Tolerability in People with Crohn’s Disease in a New Zealand Study. Foods Health Dis. 2012;2:460–486.

- Laing B., Han D.Y., Ferguson L.R. Candidate Genes Involved in Beneficial or Adverse Responses to Commonly Eaten Brassica Vegetables in a New Zealand Crohn’s Disease Cohort. 2013;5:5046–5064. doi: 10.3390/nu5125046.

- Petermann I., Triggs C.M., Huebner C., Han D.Y., Gearry R.B., Barclay M.L., Demmers P.S., McCulloch A., Ferguson L.R. Mushroom Intolerance: A Novel Diet-Gene Interaction in Crohn’s Disease. J. Nutr. 2009;102:506.